Bara Manga: Everything You Need To Know About

What is Bara Manga?

Bara is a colloquialism meaning gay manga, a type of Japanese art and media popular in Japan. The genre concentrates on male same-sex love as imagined by homosexual men for a gay man audience. The visual style and plot of Bara can vary, but it often shows masculine males with varying degrees of muscle, body fat, and body hair, similar to bear or bodybuilder culture. While bara is primarily pornographic, it has also shown sentimental and autobiographical subject matter, recognising the various emotions to homosexuality in modern Japan.

Bara Manga: Gay Manga

The use of bara as an umbrella term for homosexual Japanese comic art is mostly a non-Japanese phenomenon, and its use is not uniformly approved by gay manga writers.

Etymology: Bara Manga

Bara is a term used in non-Japanese contexts to denote a wide range of Japanese and Japanese-inspired homosexual erotic media, including illustrations published in early Japanese gay men’s publications, western fan art, and gay pornography with human actors. Bara is separate from yaoi, a Japanese media genre that focuses on homoerotic relationships between male characters and was historically created by and for women.

The best lapel pins for TV shows, movies, anime, and manga!

In order to promote their efforts, more TV networks, production companies, movie distributors, comic book companies, and anime creators are using custom pins than ever before. If you are a loyal fan of gay comics or a comic company operator, you must not miss CustomPins.CA‘s pin custom for popular comics. You can also customize pins with different images and text for you or your fan-favorite quest characters. You can design it yourself or have them design it for you for free. You can trade manga and anime pins at major events like various parties every year.

The name bara, which translates literally to “rose” in Japanese, has historically been used as a derogatory epithet for gay males in Japan, roughly equal to the English phrase “pansy.” Beginning in the 1960s, Japanese gay media reappropriated the term, most notably with the 1961 anthology Ba-ra-kei: Ordeal by Roses, a collection of semi-nude photographs of gay writer Yukio Mishima by photographer Eikoh Hosoe, and later with Barazoku in 1971, Asia’s first commercially produced gay magazine. In the 1980s, the term bara-eiga (“rose film”) was also used to describe gay cinema.

By the late 1980s, as LGBT political parties in Japan began to emerge, the term had fallen out of favour, with gei replacing it as the standard terminology for persons who had a same-sex attraction. The phrase was revived as a derogatory in the late 1990s, coinciding with the advent of online message boards and chat rooms, when straight website managers referred to the gay areas of their websites as “bara boards” or “bara chat.” Non-Japanese users of these websites later adopted the name, believing that bara was the legitimate categorization for the photographs and artwork uploaded on these forums.

Misappropriation of bara manga

This misappropriation of bara by a non-Japanese audience has sparked debate among LGBT manga writers, with many expressing unease or confusion over the term being used to describe their work. Gengoroh Tagame, an artist and historian, has described bara as “a very negative word with bad connotations,” though he later clarified that the term is “convenient for talking about art that is linked by characters that are muscle-y, huge, and hairy,” and that his objection was the term’s use to describe gay manga creators.

While artist Kumada Poohsuke does not find the name insulting, he does not characterise his work as bara since he associates the term with Barazoku, which highlighted bishnen-style artwork rather than macho artwork.

Bara Manga: Representations of homosexuality

Representations of homosexuality in Japanese visual art date back to the Muromachi period, as evidenced by Chigo no sshi (, a collection of pictures and stories about relationships between Buddhist monks and their adolescent male acolytes) and shunga (erotic woodblock prints originating in the Edo period).

While these works appear to depict male-male sexual relations, artist and historian Gengoroh Tagame question whether the historic practices of sodomy and pederasty depicted in these works are analogous to modern conceptions of gay identity, and thus part of the artistic tradition to which contemporary gay erotic Japanese art belongs. Tagame sees musha-e (warrior’s images) as a more direct antecedent to gay manga graphic styles: unlike pederastic shunga, both gay manga and musha-e depict manly men with developed muscles and thick body hair, frequently in cruel or violent circumstances.

Bara Manga: Early sexual periodicals in the 1960s

While sexual artwork was prominent in the early gay Japanese publications, particularly the 1952 private circulation magazine Adonis current gay erotic art as a medium in Japan may be traced back to the fetish magazine Fuzokukitan.

Fuzokukitan, which was published from 1960 to 1974, had gay content alongside straight and lesbian content, as well as essays on homosexuality.

The magazine featured early gay erotic artists Tatsuji Okawa, Sanshi Funayama, Go Mishima and Go, Hirano, as well as unauthorised reproductions of illustrations by homosexual Western artists such as George Quaintance and Tom of Finland.

Bara, the first Japanese magazine oriented solely at gay men, was founded in 1964 as a members-only, small-circulation publication.

Tagame describes gay erotic art from this era as “darkly spiritual male beauty,” with an emphasis on grief and sentimentalism. Men from “Japan’s traditional homosocial sphere,” such as samurai and yakuza, commonly figure as subjects. Tamotsu Yat and Kuro Haga’s homoerotic photography had a huge influence on the first wave of gay artists that appeared in the 1960s, with very little Western influence visible in these early works.

Bara Manga: Commercialization of genres in the 1970s and 1980s

Erotic periodicals geared specifically at a gay male audience proliferated in the 1970s, beginning with Barazoku in 1971 and continuing with Adon and Sabu in 1974, contributing to the decline of broad fetish magazines such as Fuzokukitan. These new magazines included gay comics in their editorial content; early serialisations were Gokigeny (“How Are You”) by Yamaguchi Masaji in Barazoku and Tough Guy and Makeup by Kaid Jin in Adon. Due to the financial success of these magazines, spin-off publications focusing on photography and graphics were created: Barazoku published Seinen-gah (“Young Men’s Illustrated News”), while Sabu launched Aitsu (“That Guy”) and Sabu Special. Barakomi was the most notable of these spin-offs.

By the 1980s, gay lifestyle magazines that published articles on gay culture alongside erotic material had grown in popularity: The Gay was founded by photographer Ken Tg, MLMW was founded as a lifestyle spinoff of Adon, and Samson was founded in 1982 as a lifestyle magazine before shifting to content focused on fat fetishism. By the end of the decade, most publishers had closed their spin-off and extra publications, however homosexual periodicals continued to publish gay artwork and manga.

Bara Manga: More on Commercialization of genres in the 1970s and 1980s

Sadao Hasegawa, Ben Kimura, Rune Naito, and George Takeuchi were among the painters who debuted during this time period, although their styles and subject matter differed greatly. Nonetheless, their work was linked by a less sombre tone than that of the artists who debuted in the 1960s, a development Tagame attributed to the steady decline in the perception that homosexuality was shameful or aberrant. In terms of subject matter, their work was also more obviously influenced by American and European gay culture, with sportsmen, jockstraps, and leather clothes appearing more frequently than yakuza and samurai.

Tagame attributed this transition to the increased availability of American gay pornography for use as reference material and inspiration, as well as the growing popularity of sports manga, which highlighted themes of masculinity and masculinity.

1990s: G-men and aesthetic changes

The trend toward lifestyle-focused publishing continued throughout the 1990s, with the publication of Badi (“Buddy”) in 1994 and G-men in 1995. Both of these publications featured editorial coverage of LGBT pride, club culture, and HIV/AIDS-related themes, as well as gay manga and other sensual content. G-men was co-founded by Gengoroh Tagame, who made his debut as a gay manga artist in 1987, drawing manga for Sabu, and who would go on to become the medium’s most importantly creative.

Tagame made a concerted effort to “alter the status quo of gay magazines” by moving away from the aesthetic of bishnen—delicate and androgynous boys and young men common in homosexual media at the time—and toward the representations of masculine males that gay manga is now identified with. The “bear-type” look pioneered by Tagame’s manga in G-men is credited with causing a dramatic stylistic shift in Tokyo’s gay area, Shinjuku Ni-chme. Following the publishing of G-men, the popular “slender and smooth” clean-shaven style among homosexual men was replaced by “stubble, beards, and moustaches. Extremely short hair became the most popular hairstyle, and the broad strong figure, which quickly morphed into pudgy and downright fat, became extremely stylish (Bara Manga).

Things One Should Know?

During this time, manga culture had a tremendous influence on homosexual erotic artwork, and gay manga occupied a central place in the editorial material of both Badi and G-men. G-men, in particular, acted as a breeding ground for burgeoning gay manga talent, launching the careers of artists such as Jiraiya. The journal also encouraged consistent readership by presenting serialised stories, which enticed readers to buy each issue. Adon, on the other hand, deleted all pornographic material from the magazine; however, the move was unsuccessful, and the journal collapsed in 1996.

The decrease of magazines and the rise of “bara manga” from the 2000s to the present.

By the early 2000s, gay magazines had fallen out of favour, as the personal advertisement sections that drove sales for many of these publications were displaced by telephone personals and, later, internet dating. In the following two decades, nearly all of the main homosexual magazines went out of business: Sabu in 2001, Barazoku in 2004, G-men in 2016, and Badi in 2019. Only Samson is still alive and well in 2021. As homosexual magazines faded, new forms of gay art evolved from contexts unrelated to gay periodicals.

A Look

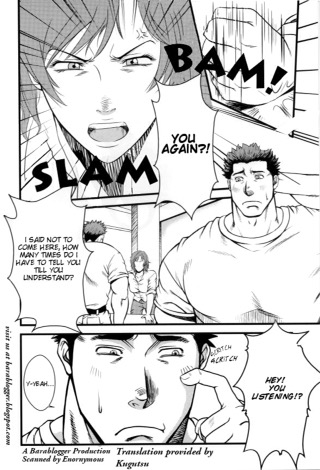

Bara Manga does give the look about handsome hunks who do work hard to stay at the gym for keeping an impact in the very best way. Hence, they do look fit and fine. This can be seen as an anime that would make many feel that fitness at any age is good for the betterment of the human body and create a magical outlook.

More Information

In Japan, pamphlets and flyers promoting LGBT events and education campaigns began to incorporate vector artwork that, while not overtly pornographic, was stylistically and structurally similar to gay manga. As new venues and settings that accepted the display of homosexual erotic artwork appeared, art shows became an avenue of expression as well. Because there were no viable big print options, many gay manga artists began self-publishing their works as djinshi (self-published comics).

Gay manga artists such as Gai Mizuki emerged as prolific djinshi authors, producing slash-inspired derivative works based on media phenomena like as Attack on Titan and Fate Zero (Bara Manga).

More on The decrease of magazines and the rise of “bara manga” from the 2000s to the present:

Beginning in the 2000s, LGBT manga began to gain international traction due to the widespread distribution of pirated and scanlated artwork on the internet. A scanlation of Kuso Miso Technique, a 1987 one-shot by Junichi Yamakawa [jp] first published in Bara-Komi, became renowned as an internet meme around this time period. Among this international audience, the name bara emerged as a way to separate homosexual erotic art created by gay men for a gay male audience from yaoi, or gay erotic art created by and for women.

The internet distribution of these works resulted in the establishment of an international bara fandom and the rise of non-Japanese homosexual erotic artists who began to draw in a “bara style” influenced by Japanese erotic art. This period also saw an increase in the popularity of kemono (, “beastmen,” or anthropomorphic figures similar to the Western furry subculture) as subjects in the gay manga, a trend Tagame credits to appearances of this type of character in video games and anime (Bara Manga).

Concepts and Themes

Gay manga is often classified by the body shape of the characters shown; common terms include gacchiri (, “muscular”), gachimuchi (, “muscle-curvy” or “muscle-chubby”), gachidebu (, “muscle-fat”), and debu (, “fat”). While the popularity of comic anthologies has encouraged lengthier, serialised stories, the majority of homosexual manga stories are one-shots. BDSM and non-consensual sex are common topics in the homosexual manga. as are stories about relationships based on age, status, or power dynamics.

For sexual reasons, the younger or subordinate character, while some homosexual manga novels twist this relationship by depicting a younger, physically smaller, typically white-collar guy as the dominant sexual partner to an older, larger, generally blue-collar man. The bottom in homosexual comics, like yaoi, is frequently represented as bashful, hesitant, or unsure of his sexuality. As a result, much of the criticism levelled at yaoi — sexism, a concentration on rape, the lack of Western-style gay identity – is also levelled at gay comics.

Also Read: Blue Lock Manga | Manga Panels | Haley Cureton | Lillie Haynes | Charles Leclerc Net Worth | Bara Manga on Instagram